Yarisal & Kublitz

Surfing the web without getting wet

{LANG:Ronnie Yarisal:de and Katja Kublitz sallied forth to an extensive expedition to the internet. They work the new symbols and peculiar topics that they discovered into elaborate sculptures. Precious materials like tourmaline, brass, and mahogany meet iPods, cigarettes, Mercedes stars, and tampons—and appear both mystic and auratic, as though they originated from temples from long gone times. Physically tangible Yarisal & Kublitz reflect our visual culture in a pointed and humorous way.

…and now: quickly forget everything we just revealed to you—Yarisal and Kublitz aren’t supposed to be creating artists at Surfing the Web Without Getting Wet but researching scientists. Cultural anthropologists to be more precise. And thus, the project does not begin in the exhibition rooms, that make you feel like you are suddenly transported to an archeological museum, but with this unusual press release following the idea of Yarisal & Kublitz.

During their thoroughly planned field research from 2012 to 2016, the cultural anthropologists Yarisal & Kublitz studied the internet. What they discovered—many exotic and seemingly conflicting phenomena—surprised and overwhelmed them at the same time. Katja Kublitz, who describes her mode of operation and methods as an experimental branch of anthropology with a special focus on transtemporal connections, exuberantly: “We all know what’s out there, but the rich, opulent intensity and the kitschy vulgarity is hard to capture.” In an early stage of their research, they decided against the intense study of a topic and elected to let themselves be carried everywhere and nowhere the web will take them. It’s a state of passive drifting analogous to the day-to-day experience of surfing through the web without direction. The aimlessness becomes the principle and simultaneously becomes the subject of their field research.

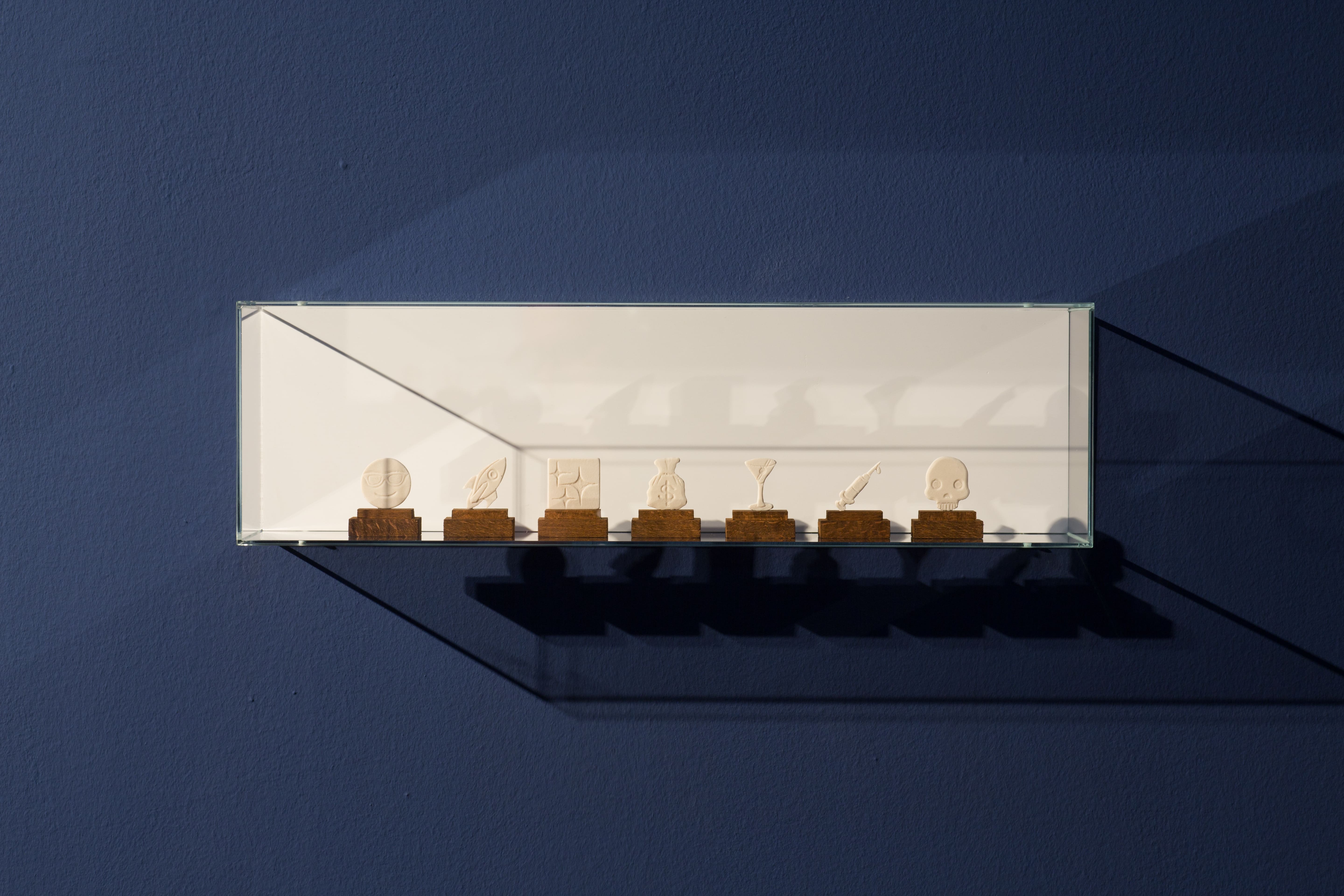

At their return, Yarisal & Kublitz brought a series of astounding artifacts and mysterious signs with them that are supercharged with conflicting associations. To their own astonishment they found that every artifact has two temporal determinates—one historic and one contemporary, which both have lost their exact classification of time and space to the unending expanses of the internet. Like in Yarisal’s & Kublitz’s earlier research of traditional cultures, many objects originate from a mystic and religious context, their exact function, however, often stays unclear. With their displacement into a space of aesthetic ‘Alterity’ the internet took theses objects’ origin. In doing so, an anachronistic mythos of indigenous inviolacy is revealed and paradoxically gets replicated again and again. Today, these artifacts get presented as curiosities and exploits of colonialism, as rare and exotic souvenirs from cultures, that through the development of our technological wins to be everywhere at the same time and visually occupy the past and future simultaneously were destroyed forever.

Kunstpalais exclusively present contemporary art—and no artefacts of anthropological research. However, the team in Erlangen was so enthused by the objects that Yarisal & Kublitz collected on their expedition that it decided to expand the museum’s program. The exhibition display the entertaining, diverse and fascinating collection of peculiar, handmade ceremonial objects and intricate, mystic sculptures that Yarisal & Kublitz were able to recover on their extensive trip through the internet.

In their collection they reveal the new politics of the origins in a global net-economy of disembodied signs and signifier. The scientists expected to return with an index of immaterial objects—inconsequential avatars of the flashing, neon colored internet trash. They were all the more surprised when they returned home loaded with a series of hand-carved artefacts, that were in their rich, everlasting materiality absolutely overwhelmed: relicts made from polished brass, precious wood and gemstones—heavy, primitive and in some cases classic talismans of the new system of forms of the network.

The idea to compile such a curious mixture of archeological objects, especially today, makes sense. With this collection, Yarasil & Kublitz enable us an unorthodox look at the random and the commonplace and allow to leave the traditional categories of the museum behind. Now, through the prism of these unexpected objects, we can have a different view on the internet and possibly take on its opaque new forms of representation, while its own confusing ‘natural history’ works like a series of enormous unconstrained experiments.