Screenprint on cardboard, two-part work

Dimensions: 84 x 59 cm each

Signature, inscriptions, markings: each signed, numbered and dated at lower right

Copy Number: 32/100

Publisher: Edition Tangente, Heidelberg

Accession Number: 1000172.1-2

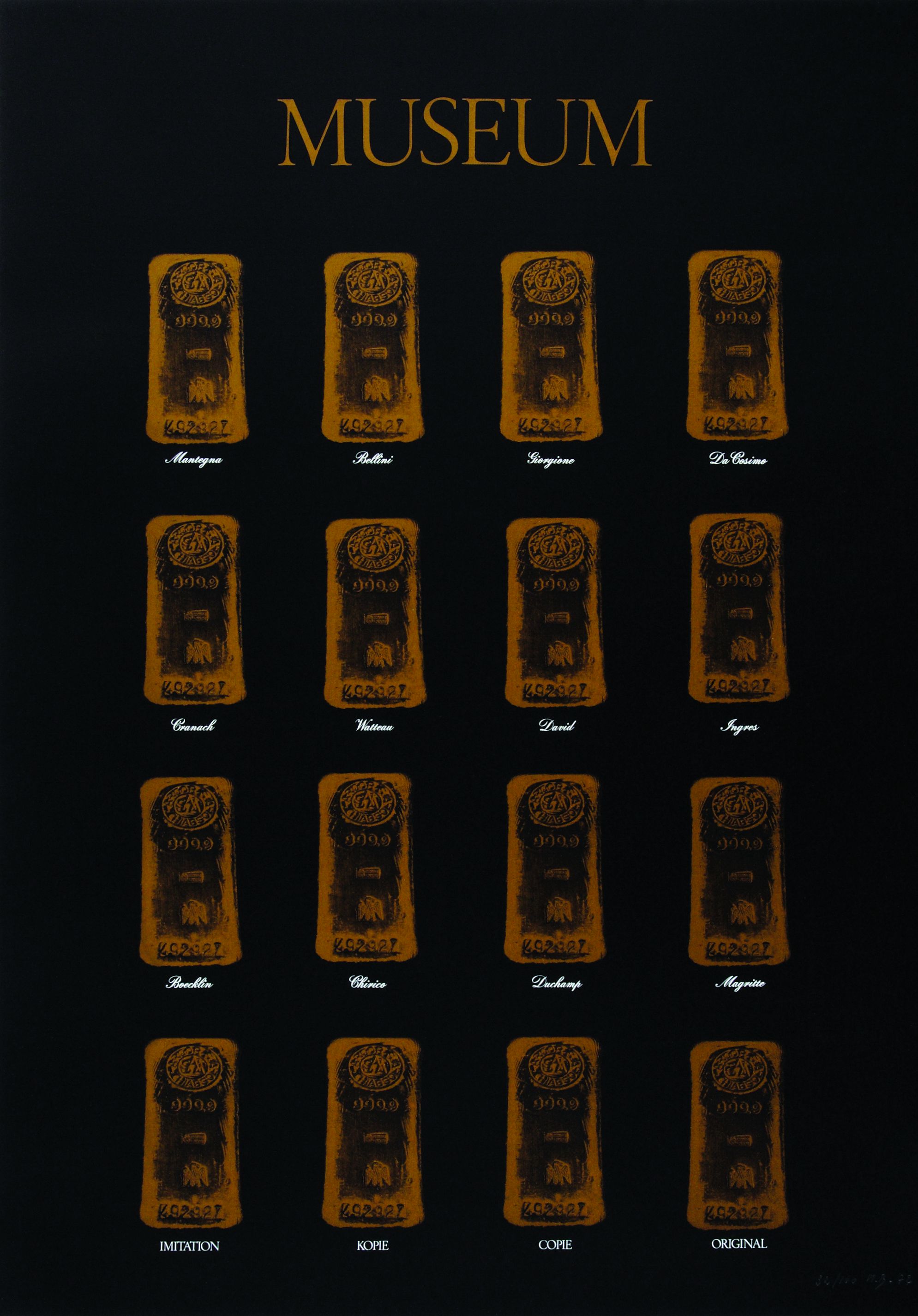

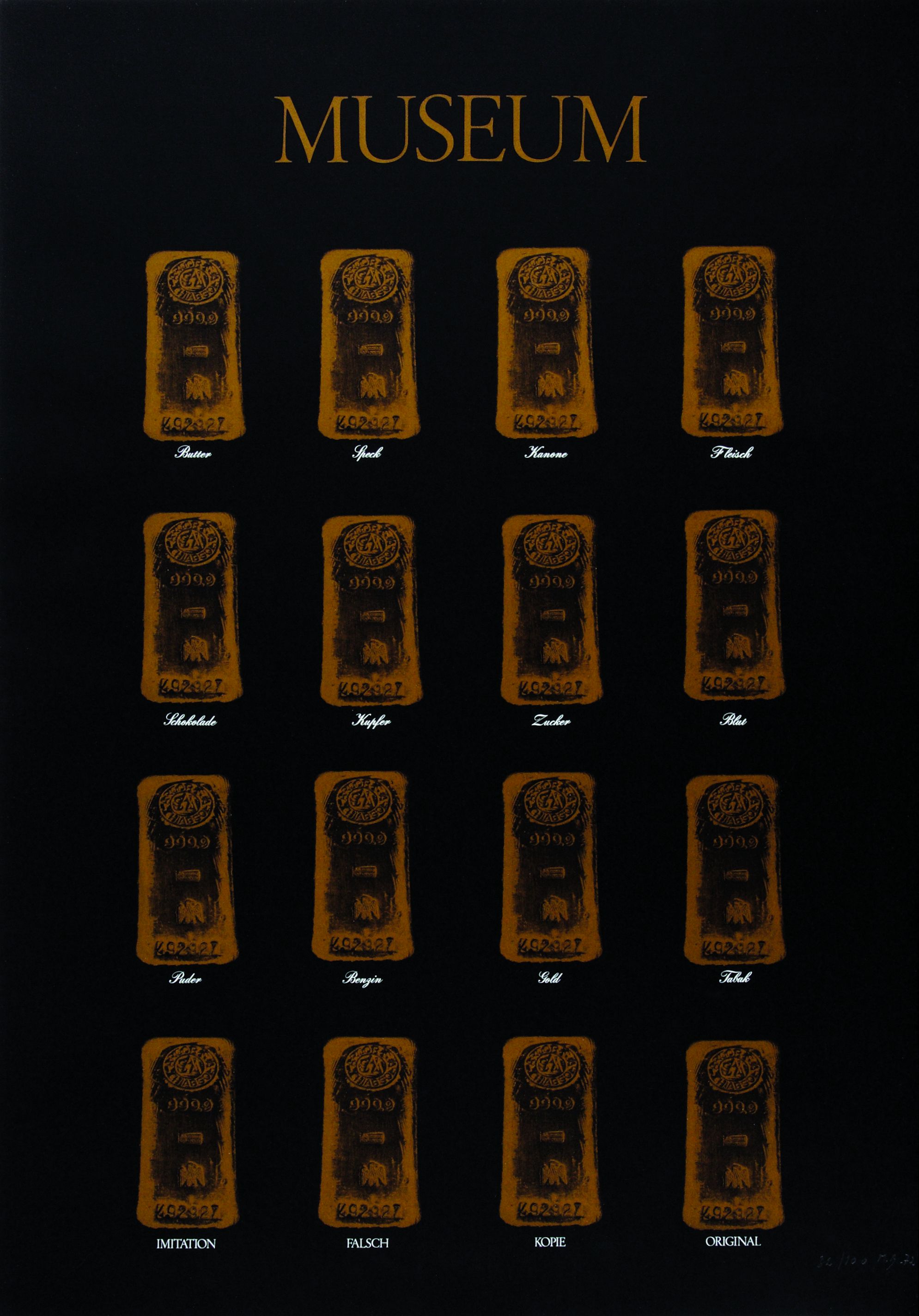

On the diptych by Marcel Broodthaers, images of golden-brown shimmering gold bars with seal-like eagle relief line up under the lettering MUSEUM, in four by four lines, like exhibits against a black background. Each gold bar bears a white signature. On one sheet they are the names of famous artists such as Mantegna, Cranach, Chirico or Magritte, on the other sheet names of consumer goods, for example butter, gasoline, copper or tobacco. However, the last row deviates from this scheme. Instead of in cursive, the following words appear here in capitals: IMITATION, FALSE, COPY, ORIGINAL on the sheet with the consumer goods; IMITATION, COPY, COPIE, ORIGINAL on the sheet with the artists' names.

The value of art and the institution of the museum, respectively, are central themes in Marcel Broodthaers' oeuvre as a whole. "He makes the mechanisms of the art market the leitmotif of his work: the work of art as a commodity, every work a mirror of its marketing."¹ Is there art everywhere where it says museum? Do names like Giorgione or David still refer primarily to "art" or have they not long since entered the so-called culture industry? Their works are exhibited as originals, but they can often be seen in everyday life as reproductions, imitations, and copies. They are used as postcards and posters, in calendars and magazines, not infrequently also for advertising. On the other hand, everyday objects can be elevated to the status of art, for example by Marcel Duchamp, who exhibited a simple urinal turned upside down under the title "Fountain," or by Joseph Beuys, who used materials such as honey or fat as carriers of meaning in his art. Do everyday things turn into art as soon as museums are placed above them? Does the value of art depend on an institution that presents it?

In Broodthaers' work, are the gold bars to be understood as the actual works of art, as exhibits under the heading of museum, or do they only symbolize the "value" of the names listed underneath? Does Broodthaers, like his model René Magritte, also play with different systems of representation? Artists and goods are represented both by characters and by gold ingots; gold continues to stand for power and wealth, as does the stamp with the eagle symbol. The eagle embodies struggle, pride, loneliness, and recurs in the artist's work like a signature or trademark.

Gold can be exchanged for money, money for goods. But what about art? It, too, is marketed. Similar to the brands on consumer goods, it is usually the signature, i.e. the name on the original, and not the work itself that makes up the actual value. Museum visitors often first look at the inscriptions on a work of art and base their value judgment on them, even before they turn their attention to the painting itself. Does the artist's name or the commercial value or the fact that the work is in a museum constitute art? These are all questions that Broodthaers' art raises. He himself critically remarks: "What is art? Since the 19th century, this question has been asked continuously of the artist, the museum director, as well as the art lover. I actually doubt that it is possible to give a serious definition of art as long as we do not examine the question under a constant, I mean the transformation of art into commodity."² The concern of his semiotic art is to understand "art" no longer from its supposed substance, but in the relativity of its value.

Sarah Wittig

¹ Heinz Peter Schwerfel, Rückkehr in der Heldenklasse, in: Art. Das Kunstmagazin, 6, 1997, S. 34.

² Dorothea Zwirner, Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976), Kunstraum München e.V. und Raum für Kunst e.V. Hamburg, München 1992, S. 13.